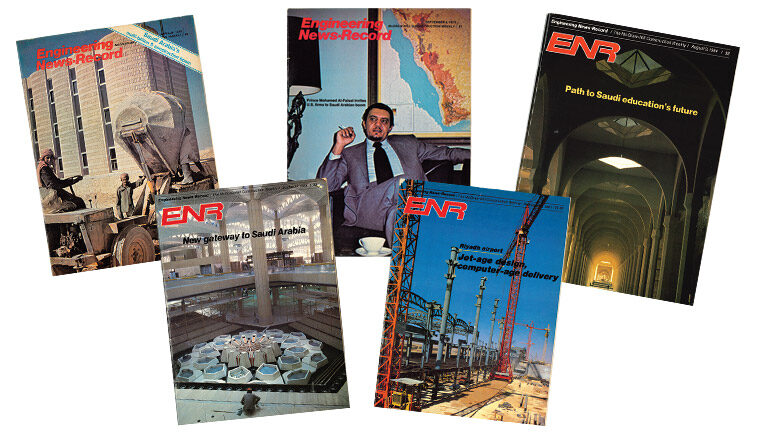

Saudi Buildout Launched Many US Firms into Global Markets

[ad_1]

Saudi Arabia was an underdeveloped country in the 1960s when its ruler, King Faisal, embarked on a far-reaching modernization drive. Faisal’s initiatives involved constructing all kinds of infrastructure and the creation of now-essential industries such as petrochemicals, iron, steel, cement and mining.

By 1975, the Army Corps of Engineers’ Saudi Arabia District office was overseeing an $8-billion portfolio ($48 billion today), encompassing housing, highways, airports, hospitals, schools, office buildings, factories, military installations, power plants, sewage treatment plants, desalination plants, ports and refineries. Specifications called for the installation of U.S.-made equipment and required that all design work go to U.S.-based design firms, but construction contracts were open to international bid competition.

A major stumbling block for U.S. contractors to bid on this work was a Saudi requirement that a 10% performance bond be placed in a Saudi bank as a guarantee on every public project. That contractual requirement drained U.S. firms’ lines of credit and discouraged many from entering the rapidly growing Saudi market. After the intercession of U.S. trade groups the Associated General Contractors of America, the National Constructors Association and the International Engineering and Construction Industries Council, the Saudi government let contractors put up surety performance bonds instead. This swung the gates wide open.

Foreign contractors getting started in Saudi Arabia faced severe challenges. Every piece of construction equipment had to be imported, and except for aggregate, asphalt and some cement, so did all the materials. Equipment and material could only enter through two ports, and delays of four to six weeks were common. The local workforce supply was severely low, so contractors brought in workers from other Arab countries as well as Pakistan, South Korea and the Philippines.

A cornerstone of the development program was a $7-billion network of desalination plants combined with natural gas power plants, which would supply water to refineries, industrial plants and newly built communities. Prince Mohammed Al-Faisal, who was in charge of energy and desalination programs expected to total $45 billion over five years, visited the U.S. to pitch industry firms on the burgeoning market opportunities. The first American consortium to compete was made up of Blount Bros. Corp.; Chas. T. Main Inc.; General Electric Co.; Combustion Engineering Inc.; Chicago Bridge & Iron Co.; and Newport News Industrial Corp.

Jubail, a small fishing village on the Persian Gulf in 1975, was transformed into a 360-sq-mile industrial colossus, boasting a major international port, a steel mill and aluminum and fertilizer plants along with the necessary housing, highways, power and water infrastructure. Developed by Bechtel, it grew into one of the world’s largest petrochemical complexes, and was home to 70,000 residents by 1992. Massive earthmoving for flood protection was performed. Additionally, “fill is needed to cover large expanses of subkah, a weak silt, sand and clay mixture that has a high water table,” a 1978 ENR article reported. “At times during the three-month Saudi wet season, even bulldozers get mired in this material. One Saudi engineer recalls watching a car disappear after it ran off a road into the subkah.” The construction workforce was expected to grow to 40,000 by the mid-1980s. Today, Jubail’s population is 500,000. A 1985 ENR cover story on the city reported that the Guinness Book of World Records judged Jubail to be the largest construction project in history.

Yanbu, a sister project to Jubail, was sited on the Red Sea coast, and offered much more direct shipping routes to European customers. The Ralph M. Parsons Co. completed the master plan, managed the design and construction of infrastructure and established requirements for the firms that would build the industrial plants. It included two refineries, a natural gas liquids plant and terminal, steel mill, aluminum smelter, deepwater oil terminal and airport. Two 800-mile pipelines supplied the feedstock to the refineries: a 48-in.-dia oil pipeline with a capacity of 2.4-million barrels per day, and a 26-in. to 30-in.-dia natural gas liquids line. By 1981 the construction workforce had reached 23,000. A 1983 ENR article pegged the project’s cost to reach $26 billion by 1985, with the population expected to rise to 50,000. Today the city of Yanbu is home to 260,000 residents.

A comprehensive scheme of military projects was conceived, including two naval bases, several academies, and four major bases. King Khalid Military City (KKMC), a 220-sq-mile, octagon-shaped greenfield project in the country’s northeast, became home to 70,000 servicemen, families and support personnel. It housed three brigades and the Saudi combat engineering school. The work was split into 34 separate contracts, in order to enable mid-sized firms to compete. The world’s largest precast concrete plant churned out elements as large as 41 tons, and produced insulated sandwich wall panels designed to keep out the desert heat. KKMC had 4,500-ft-deep wells to supply water, its own airport, and its own port 180 miles away on the Gulf to bring in materials and equipment. The workforce for the $9-billion project peaked at 20,000.

Riyadh’s King Khalid International Airport featured five triangular terminals, designed by Helmuth, Obata & Kassabaum, plus a 5,000-person hexagonal mosque and one of the tallest control towers in the world. Bechtel handled the master planning, as well as providing a sophisticated logistics system for shipping materials and equipment ordered by the 66 individual contractors. Logistics control offices in San Francisco, Baltimore, Rotterdam and Tokyo tracked shipments from suppliers to the port of Damman, through customs, and finally by truck or rail for the final 220-mile leg. The workforce peaked at 12,000, and it began operating in 1983.

Jeddah, on the Red Sea, is the point of entry for foreign pilgrims participating in the annual Hajj to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. The volume of international pilgrims grew rapidly, from 100,000 in 1950 to nearly 500,000 arriving by air in 1975. U.S. firm Airways Engineering Corp. got the airport design contract in 1965, and engaged Edward Durrell Stone Associates to design the main terminal building. The project went dormant as the Saudis applied their attention and funds to the 1967 Six-Day War. Hochtief won the construction contract in 1974, but the International Civil Aviation Authority stepped in and recommended expanding the terminal, forcing a redesign. The Saudis agreed, and subsequently added an even larger expansion. Skidmore, Owings & Merrill was invited to join the design team, and a Parsons-Daniel joint venture was brought on board as CM. Minoru Yamasaki was invited to design a royal pavilion. The workforce swelled to 10,000 and the price tag ended up at $4.3 billion.

The airport’s distinctive feature was a 105-acre fabric-covered roof, offering shelter to the masses of pilgrims making their way from immigration and baggage handling to food services and rest areas and then on to the bus terminal. It is comprised of 210 tent-like roof units of Teflon-coated glass fiber fabric made by Owens Corning, each 148 ft sq, supported by 148-ft-tall pylons and cables.

King Saud University, an educational showpiece, was designed by a joint venture, HOK + 4. Able to accommodate 21,500 students, the 2,400-acre campus comprised densely arranged low-rise buildings constructed using a repetitive modular system of precast concrete elements. Chief designer Gyo Obata employed elements of traditional Najd architecture of central Arabia, such as clustering buildings close together to provide shade, and narrow windows to keep out hot sunlight. The campus’s main walkways are covered by canopies of precast concrete arches and palm-like columns. Tan concrete resembled unbaked mud used in traditional Najdi buildings. The French-American joint venture of Bouygues and Blount International Ltd. built 6.7 million sq ft of academic buildings in less than 40 months. The project’s bill was $4 billion.

By 1977, the Corps’ Middle East Division was managing a $17-billion program of Saudi projects. The division employed 743 civilians and 67 military staff, split between offices in Berryville, Va., and Riyadh. The program opened doors for U.S. firms to a wide range of private-sector work in the kingdom. In recognition of his leadership role in supporting U.S. firms expanding internationally, the editors of ENR chose to give its 1977 Award of Excellence to Lt. Gen. John W. Morris, Chief of Army Engineers from 1976-80.

[ad_2]

Source link

Post a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.