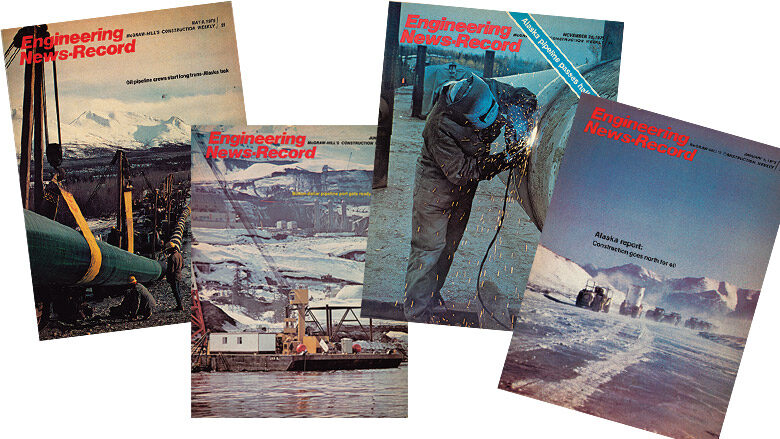

Massive Mobilization Forged the Trans-Alaska Pipeline

[ad_1]

Moving hot oil across Arctic terrain was an unprecedented challenge following the discovery of America’s largest oil field in 1969 in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. The first hurdle the Trans-Alaska Pipeline had to clear was environmental approval. The National Environmental Policy Act was passed in 1969, the same year Alyeska Pipeline Service Co., a consortium of seven oil companies, announced plans to build the pipeline. NEPA required the Interior Dept. to produce an environmental impact statement for the project, which ran to 12,000 pages. Public hearings and court challenges played out over four years. In late 1973, following the OPEC oil embargo, Congress overrode further delays and cleared the pipeline from any more NEPA-related court challenges.

The pipeline’s 796-mile route south from Prudhoe Bay crosses three mountain ranges, 20 major rivers and 300 streams before reaching the ice-free port of Valdez. The highest point, at 4,800 ft, was Dietrich Pass in the Brooks Range. As the first-ever oil pipeline in the Arctic it posed serious design challenges. Seismic and ground conditions were not ideal. Some 420 miles of the route was over permafrost. The pipeline could not be buried in those areas as the heat of the oil would melt the permafrost, turning it into a slushy mass with no bearing capacity. The aboveground line rests on 36,000 steel bents and runs in a zigzag pattern, allowing up to 20 ft of horizontal and 3 ft of vertical pipe movement so it can endure earthquakes. Every 700 ft to 1,800 ft the pipes are clamped firmly to anchor assemblies to prevent horizontal movement. Between the anchors the pipes are mounted in sliding shoe assemblies.

Alyeska chose Bechtel as construction manager for the pipeline and haul road, and Fluor as CM for the 12 pumping stations and a tanker terminal at Valdez. Five contractors were each awarded segments of the pipeline itself, which had been designed by Michael Baker International. Bechtel stationed 500 employees in Fairbanks. Early on, Alyeska admitted to start-up delays, some due to a lag in delivery of drill rigs and drill bits, as well as a slow start on the Valdez oil tanks. A shortage of mechanics and welders and a high turnover among laborers presented further difficulties. A 1975 ENR article stated: “Many contractors continue to blame construction problems on the relationship between Alyeska and Bechtel.” Alyeska ended Bechtel’s role as CM, and issued a new contract that designated the firm as “construction/technical services manager.”

The 84,000 bent piles had to be driven below the permafrost thaw area to provide adequate bearing—anywhere from 22 ft to 50 ft deep. Despite thousands of test borings and soil samples, geotechnical surprises meant drilling gear was often mismatched to soil conditions, causing expensive delays. Since the 48-in.-dia pipe was mounted only 2 ft above grade, it posed a barrier to local wildlife. There are 554 locations with higher clearances to serve as animal crossings.

Initial construction in 1974 saw completion of a two-lane gravel haul road running 350 miles from the Yukon River to the North Slope. The 28-ft-wide road embankment was 5 ft thick to protect permafrost. Crews also built gravel work pads for the 5,000 pieces of equipment and 29 work camps, each with a 5,000-ft gravel airstrip. By December 1974, there were 3,000 workers engaged in drilling holes for piles, finishing concrete footings for the Yukon River Bridge and blasting rock at Valdez to gouge an oil tank platform out of a mountain.

As a condition for obtaining a permit to build a pipeline that traversed federal land for over two-thirds of its route, Alyeska agreed to an extensive federal and state surveillance effort to ensure environmental safeguards were met. The Interior Dept. and state monitoring teams totaled 95 staffers, who had the right to stop work if necessary, and did so several times.

Hiring ramped up in the spring of 1975 and the workforce peaked at 21,600 that September, dropping by more than half the following winter, with the cycle repeating in 1976.

Workers were trained in Arctic survival by two former U.S. Army sergeant majors with Arctic experience. Some points mentioned in a 1975 ENR article include: “Warm water or urine can free bare hands that have quickly frozen to tools or other metal … shelters can be dug in snow if workers are trapped outdoors … anyone who leaves camp must travel with at least one other person.” Anyone traveling by vehicle had to carry a sleeping bag in case of being stranded. Recognizing that long working hours, cold winters and limited recreation could foster alcoholism among the workforce, a union-contractor initiative encouraged supervisors to intervene and steer candidates into 12-step recovery programs rather than fire them.

One of the first sections of pipe placed was a 1,900-ft section across the Tonsina River and its adjacent flood plain. Thirteen sideboom tractors walked the vinyl-wrapped pipe out on a 40-ft-wide gravel work pad and placed it in a water-filled trench up to 17 ft deep. The 300 ft of pipe under the active river channel had a 9-in.-thick protective concrete coating. Nine-ton concrete saddle weights pinned the pipe in position to counteract buoyancy until the line was filled with oil.

The most difficult pipelaying was at Thompson Pass in the Chugach Mountains, which had a slope of 47 °, the steepest on the route. Contractor Morrison-Knudsen had to use a kiloton of explosives to cut a 3,700-ft-long trench up the slope. A winch-driven cableway system carried spoil down and pipe sections and equipment up. Customized 92-ton tracked vehicles were used to pump fine-grained backfill material through 10-in.-dia hoses.

Union strife kicked up in 1975, despite a no-strike provision in the contract. A brief walkout of 4,200 workers over Teamsters’ grievances was ended by a court injunction. Later, almost half of the 2,000 welders walked off the job for two days after they were denied the two-week rest and relaxation period guaranteed by their contract.

An orthotropic steel box girder bridge across the Yukon River was completed four months behind schedule in October 1975. The 2,280-ft-long structure enabled heavy truck traffic to access the northern stretch of the project. It also carried the pipe on an external, cantilevered steel framework. The pipeline crossed the Tanana River on a pipeline-only bridge with two 170-ft-high towers 1,200 ft apart— Alaska’s longest suspension span.

The terminal in Valdez alone cost $1 billion to build and featured four tanker berths and 18 oil storage tanks. Workers excavated 14 million cu yd of overburden to reach bedrock. Each tank rested on an asphalt-sand-gravel cushion inside a concrete ring wall base. Welders assembled the 62-ft-high, 250-ft-dia steel structures, each holding 510,000 barrels.

Alyeska installed Frank P. Moolin Jr. as the project’s construction manager in June 1975, following Bechtel’s demotion. Moolin decentralized authority, giving field managers responsibility for making more decisions on their own. He demanded detailed productivity reports. When work stopped for any reason, Moolin decreed that crews had to be sent back to camp where they would not be paid. He started a sweepstakes competition among the five contractors, charting their progress against their goals. All this pressure helped put the project back on track.

Quality control problems plagued the project from mid-1975 through the finish line. Alyeska discovered that 8% of the manual welds in a 150-mile section of pipe had defects or deficiencies, and that numerous X-rays of welds were falsified. It set to work rechecking each of the 3,748 welds in that section, almost two thirds of which was buried, and fired the X-ray services contractor on that section. The Interior Dept. and the U.S. Dept. of Transportation’s Pipeline Safety Board ordered an independent investigation of the weld X-rays and repair records for 30,800 welds done in 1975. A whistleblower employee of the X-ray contractor testified before Congress that he was pressured to falsify X-rays. President Gerald Ford sent a federal fact-finding team to Alaska in 1976 to look into the mess. By October 1976, Alyeska had repaired all 263 substandard welds, and X-rayed them again, at a cost of roughly $2,000 per weld.

As the largest peacetime project in U.S. history, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline had an outsized impact on Alaska. Fairbanks’ population doubled in size in the first year to 60,000 from 30,000. Thirty two workers died during the course of the project.

Shortly after the last weld was made in June 1977, 27 months after the first weld, oil began flowing southward from Prudhoe Bay at about 1 mph, reaching Valdez a month later. The oil entered the pipe at 140° F, and with friction offsetting cooling, maintains its temperature even in winter.

The final cost was $10 billion, heavily impacted by high inflation and a roughly $1 billion overrun. The project met its deadline, however, and ENR cited Moolin as 1977’s ENR Man of the Year (now known as the Award of Excellence).

[ad_2]

Source link

Post a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.